The Inextricable Intertwining of Science, Technology, Religion, and Spirituality in India Across Historical Epochs

Editorial by Mathew Chandrankunnel

The relationship between science and religion in India presents a historical trajectory of profound complexity and inextricably intertwining, distinctly different from the often-observed dichotomy in Western modernity. This unique characteristic reflects the subcontinent's rich philosophical and spiritual traditions, where scientific inquiry and religious thought were traditionally viewed not as opposing forces, but as complementary pathways to understanding the universe and human existence.

This foundational perspective has shaped the epistemological framework of Indian civilization, influencing all subsequent historical periods, even when external forces attempted to impose different existential and developmental models. Hinduism, is an amalgamation of the Brahma tradition, the nomadic Saivite tradition and the agrarian Vaishnava tradition all amalgamated into the Brahma – creation, Vishnu – Sustainment and Siva – destruction Godhead with various philosophical and ritualistic traditions integrated into a web of mythologies. As Hindusim became more violent and intolerant, Siddharth Gautama initiated a nonviolent revolution which catapulted him as Sri Buddha and the religion of Buddhism evolved into a world religion which was extinct in India by the 12th century due to various reasons. However, the Buddhist scholars established universities in the beginning of the common era, first of its kind in the world such as Nalanda, Vikramsila, Odandapuri, the Buddhist centres of learning which attracted students from abroad. Later the invading armies of Islam, the colonial British powers enslaved the subcontinent and diffused its own ideological, religious, spiritual, scientific, technological advancement with positive as well as negative results. This in-depth article will comprehensively explore how this intricate relationship evolved across ancient, medieval, Mughal, British Colonial, modern, and contemporary periods, highlighting the unique syntheses, significant paradigm shifts, inherent tensions, and ongoing dialogues that define India's distinct approach to knowledge.

The initial understanding of knowledge acquisition in India was fundamentally holistic. The pursuit of truth, known as Satya, and a comprehensive understanding of the cosmos based on Ahimsa – non-violence and Aprigraha – non possessiveness was shared, unified goals for both scientific inquiry and religious thought. This meant that knowledge was not compartmentalized; rather, it was seen as a singular, holistic quest where spiritual insights could inform scientific observation and vice-versa. This overarching holistic view forms a core underlying theme that subtly or overtly influenced all historical periods. It helps explain why terms like "integration" or "coexistence" are more fitting descriptors than "conflict" for much of India's historical engagement with these domains. This foundational difference provides a crucial lens through which to interpret the unique dynamics observed across various eras.

Furthermore, the perception of both science and religion as "pathways to understanding the universe and human existence" established a direct and causal link between spiritual aspirations and scientific pursuits. If comprehending the universe was a paramount spiritual objective, then systematic scientific methods—including observation, calculation, and empirical investigation—became legitimate, valuable, and even necessary tools within that broader spiritual endeavour. This explains why sacred texts and rituals actively prompted detailed observations of the natural world, which, over time, gradually evolved into systematic scientific methods. This initial causal connection meant that scientific advancements in ancient India inherently carried spiritual or religious connotations and were integrated into a broader spiritual worldview, setting a precedent for future interactions. The splendour of the blending of the science and religion dimension is visible in and through the Yoga, an integration of the spiritual guidance with physical exercises, mental aspirations and deep meditative processes exemplifying the characteristic milieu of the philosophical, the psychological, the pneumatic scientific and technological holistic continuum.

I. The Indus Valley Civilization: A Pragmatic Urban Society as a Testament to Secular Culture, Science, and Technological Ingenuity

Indus Valley Civilization (IVC), known to be Pre-Vedic, is a profound foundational culture, devoid of any significant religious and spiritual moorings but with advanced technological developments with metric and weighing systems, multiple storied large buildings, paved walking spaces, regulating the floods with dams and sewage systems emphasizing a secular and technological heritage. The detailed enumeration of the IVC's scientific and technological achievements, such as sophisticated urban planning, water management, and metallurgy, is significant. The sheer scale and sophistication of their engineering and organizational capabilities suggest a highly advanced, empirically grounded knowledge system. This implies that the later Vedic integration of science and religion was not an ex nihilo creation, but rather a philosophical and religious overlay onto an already existing, robust tradition of practical, secular and scientific knowledge. This paradigm shift from a secular towards a religious framework couldn’t be understood in terms the available knowledge unearthed and needed further meticulous research to unravel the discontinuity from an advanced technological evolving knowledge tradition in India, with significant technological achievements towards a Vedic philosophical and religious syntheses.

Urban Planning and Architecture: Cities like Mohenjo-daro and Harappa exhibited remarkably sophisticated urban planning, characterized by grid-like layouts and well-organized streets intersecting at right angles, showcasing advanced knowledge of geometry and spatial planning. Houses were constructed using standardized baked bricks, indicating a deep understanding of construction techniques and material science. The cities also featured advanced drainage systems with covered drains, wells, and baths, demonstrating an early mastery of hydraulics and sanitation engineering.

Water Management and Sanitation: The civilization's expertise extended to elaborate drainage systems that efficiently channelled wastewater away, preventing stagnation and disease. The Great Bath at Mohenjo-daro is a prime example of their knowledge of water-tight construction, utilizing bitumen as a sealant, reflecting an understanding of waterproofing techniques. Private wells and extensive water storage facilities further underscored their mastery over hydrological engineering, providing clean water to urban populations.

Metallurgy and Material Science: The Harappans made significant advancements in metallurgy, working adeptly with copper, bronze (an alloy of copper and tin), and possibly early forms of iron. The widespread use of bronze tools and ornaments indicated a sophisticated knowledge of alloying techniques and material properties. The discovery of finely crafted tools, weapons, and jewellery reflected their profound understanding of metallurgy and material strength, which facilitated agricultural productivity and craft specialization.

Manufacturing and Craftsmanship: The civilization demonstrated high skill in various crafts, including pottery, bead-making, sealing, and metallurgy. Their pottery was highly standardized in shape and decoration, indicating a developed understanding of ceramic technology and firing techniques. Seals made of steatite, with inscribed motifs and symbols, suggested the use of advanced carving tools and a systematic approach to administration and trade. The inscriptions, although undeciphered, point to a form of proto-writing, reflecting early developments in symbolic communication and record-keeping.

Agriculture and Surplus Production: The Indus Valley people developed advanced agricultural techniques, including the use of ploughing with domesticated animals and possibly early irrigation methods. Their cultivation of wheat, barley, peas, and sesame required knowledge of crop rotation and soil management. The resulting surplus food production supported large urban populations and specialized craft industries, signifying an understanding of agricultural science and resource management.

Trade and Commerce: Trade was a vital aspect of the Indus Civilization’s scientific and technological development. They engaged in long-distance trade with Mesopotamia, exchanging goods such as beads, seals, and crafts for precious stones, metals, and luxury items. The presence of dockyards like Lothal indicates their expertise in shipbuilding and navigation, which was essential for overseas trade. Their knowledge of seafaring and maritime engineering played a crucial role in establishing extensive trade routes across the Arabian Sea.

II. Vedic Period: Science as a Sacred Inquiry to Understand the Universe

The Vedic period in India exemplifies a profound integration of science, technology, religion, and spirituality, where scientific pursuits were often considered an intrinsic part of a larger spiritual quest for truth and cosmic understanding. Ancient Indian civilization made significant advancements across various scientific disciplines, consistently operating within a deeply spiritual framework. The Vedic tradition, which forms the bedrock of Hindu philosophy, Sanatana Dharma, explicitly emphasized the pursuit of truth (Satya) and a comprehensive understanding of the cosmos. This philosophical underpinning meant that sacred texts and rituals actively prompted detailed observations of the natural world. Over time, these observations gradually evolved into systematic scientific methods. Indian philosophical schools, such as Nyaya, focused on logic and epistemology; Samkhya, a dualistic enumeration-based metaphysics; and Vedanta, exploring the ultimate reality of Brahman, significantly contributed to a worldview that inherently accommodated both spiritual and rational inquiry. The emphasis on experiential knowledge (anubhava) and rigorous reasoning (pramana) allowed for a nuanced approach where religious insights and scientific reasoning were not perceived as mutually exclusive but rather as complementary avenues to knowledge. This intellectual environment fostered logic and free thinking, considering contemplation and direct experience as legitimate methods for acquiring knowledge. This period was notably characterized by a pluralistic attitude, fostering an environment that accepted the coexistence of diverse values and knowledge systems. The inclusion of empirical observation (perception) and logical reasoning (inference) within the accepted pramana for understanding reality inherently legitimized scientific inquiry as a valid path to truth, even if the ultimate truth (Brahman) was considered to transcend purely empirical grasp. This philosophical grounding provided the necessary intellectual space for science and religion to coexist and complement each other, as both were seen as contributing to different, yet interconnected, aspects of a larger, holistic truth.

Scientific Advancements and Spiritual Linkages

Ancient India saw remarkable scientific and technological progress, often directly linked to religious and spiritual frameworks. The pursuit of life was centred around the sacrifices conducted meticulously at home and public known as puja based on the correct pronunciation, correct language, selecting the auspicious timing, specifically constructed with geometric precision the structures for conducting the sacrifices are significant to note a paradigm shift from the pre – Vedic towards a Vedic culture where science and technology were subservient to the religious practices and spiritual yearnings. The meticulous instructions are compiled under Vedangas, meaning "limbs of the Veda," are six auxiliary disciplines in Hinduism that aid in understanding and preserving the Vedas, known as Shiksha (phonetics), Chhanda (metrical prosody), Vyakarana (grammar), Nirukta (etymology), Jyotisha (astronomy), and Kalpa (ritual).

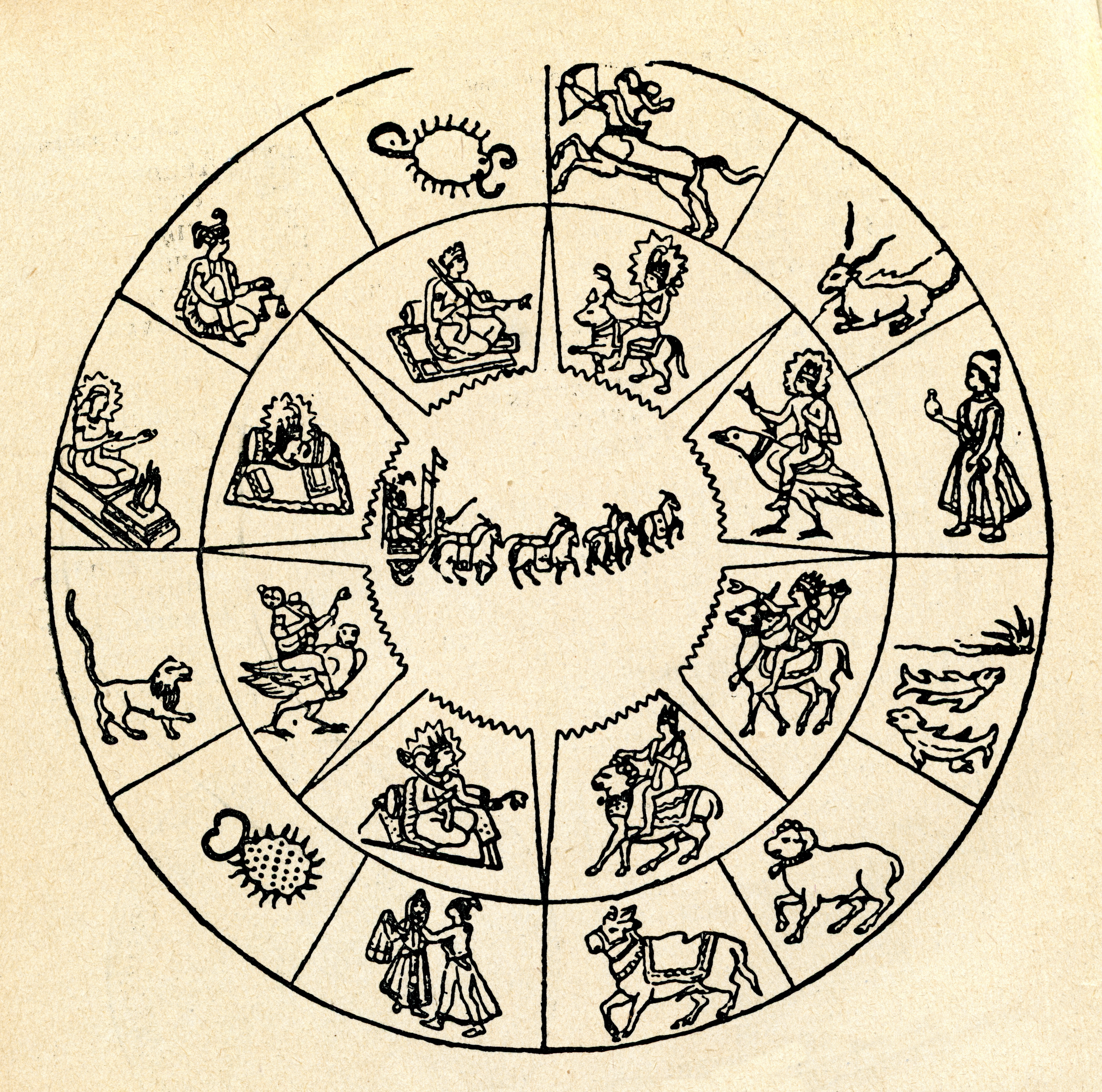

Astronomy integrated with Astrology (Jyotisha): Indian scholars like Aryabhata and Varahamira made precise astronomical observations and formulated sophisticated theories regarding planetary movements, eclipses, and the cosmos. Crucially, these astronomical insights were often directly linked to religious rituals and cosmological views deeply rooted in Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain traditions. The discipline of Jyotisha, encompassing astronomy, astrology, and mathematics, served as a vital "receptacle" for a wide array of intellectual activities, including those that would be classified as natural sciences today. Mathematics and astronomy were actively developed and utilized for religious purposes, such as calculating auspicious dates (muhurta) for ceremonies or determining marriage compatibility.

Mathematics: Indian mathematicians pioneered the concept of zero and developed the decimal system, innovations that profoundly revolutionized mathematics globally. Vedic mathematics also demonstrated advanced arithmetic and geometry.

Medicine (Ayurveda): Ayurveda, the traditional Indian system of medicine, seamlessly combined spiritual concepts, such as the balance of energies (doshas), with empirical herbal remedies and surgical techniques. Its practices clearly reflected a confluence of religious beliefs and meticulous empirical observations. Furthermore, Vedic texts contained a complex system of medicine, including early forms of inoculation.

Philosophical Schools and Vedic Insights

Beyond practical applications, Vedic texts and philosophical schools offered profound theoretical insights that intersected with scientific understanding.

Ecology: Vedic texts contained profound ecological insights, promoting a deep reverence for nature and an understanding of biodiversity. They viewed the environment as a sacred, interconnected system, emphasizing interdependence through metaphors and reverence for natural elements.

Physics: Vedic thought explored fundamental concepts of matter, energy, and natural movement, with some modern interpretations drawing intriguing and controversial connections to quantum mechanics and the role of consciousness.

Cosmology: Vedic cosmology presented multiple creation theories, including an agnostic view in the Nasadiya Sukta, and a concept of vast, cyclic cosmic epochs spanning billions of years, which remarkably aligns with some modern scientific speculative hypotheses such as bubble or big bounce theories regarding the emergence of the universe.

Atomism: The Vedic theory of atomism distinguished subtle and gross metaphysical elements, showing some intriguing parallels with atomism and equivalent to the five basic cosmic stuff elaborated by other ancient philosopher scientist from Greece.

Religiosity – Spirituality -Psychology: The sophisticated exploration of the mind, its various layers, and the nature of human life and its purposiveness highlighting an eternal life incorporating prayers for universal salvation expressed through the deeply philosophical and spiritual treatises known as Upanishads. The "Asato ma sadgamaya" mantra, a part of the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, (1.3.28) is a unique deep prayer in Sanskrit that translates to "Lead me from untruth to truth, from darkness to light, and from death to immortality." It's a plea for guidance and enlightenment that was uttered so meaningfully by the beginning of the Indian culture that signifies a unique search for the purposiveness, an acceptance of the Divine and a yearning to merge with this transcendence ultimately.

Sacralization of Secular Sciences

Intellectual activities were often monopolized by the class stratification of the society and giving it a soteriological foundation in order to keep the status quo. Manu Smriti, a sedimentation of the accumulated thoughts classified as a dialogue between Manu and Bhrigu discussed on topics such as duties, rights, laws, conduct, virtues etc. Through this manifesto women were interpreted as always accompanied by father, husband and son giving an emphasis on a patriarchal system of life. Role of Brahmins as priests enabled to conduct pujas and had given an apex status in the highly hierarchical society. Thus, Brahmins, who played a crucial role in the "sacralization" of sciences that might otherwise be considered secular. This was achieved through a process of Sanskritization, whereby non-Aryan ideas and practices were conformed to the dominant Aryan framework, integrating them into the religious and philosophical mainstream. This process was not simply about religious dominance; it was a highly effective mechanism for integrating diverse knowledge systems into the prevailing cultural and religious framework. By associating scientific practices, such as astronomical calculations for auspicious timings or medicinal practices for well-being, with religious rituals or philosophical frameworks, these practices gained immense legitimacy, patronage, and a robust means of transmission across generations. This ensured that scientific knowledge was not perceived as external, foreign, or threatening to the existing religious order but rather as an intrinsic and valuable part of it, thereby fostering its development, continuity, and widespread adoption within the society. This also implies a subtle power dynamic where the dominant religious elite absorbed, validated, and shaped the narrative around scientific knowledge, ensuring its survival within their established framework and thus effectively shielded others to acquire knowledge and practice it.

III. Medieval and Mughal India: Integrating Cultures and Ethos

The Medieval and Mughal periods in India witnessed significant shifts in the relationship between science, technology, religion, and spirituality, primarily influenced by the arrival and flourishing of Islamic scholarship. This era was characterized by a blending of knowledge systems and evolving administrative approaches to religious matters, while scientific pursuits continued to be influenced by philosophical and spiritual motivations.

During the Medieval period, there was a discernible move towards the administrative separation of religious matters, with the establishment of a distinct department for religious affairs. Scholars have historically debated whether the state during the Sultanate period was a theocracy, indicating a more complex relationship between religious authority and state governance than a simple religious rule. This suggests that while institutional structures began to differentiate functions, the underlying philosophical and practical motivations for scientific work often remained deeply intertwined with spiritual or religious worldviews. This nuanced dynamic sets the stage for later observations in contemporary India, where formal structures might suggest separation, but the lived reality and intellectual pursuits often demonstrate continued integration.

Integration of New Knowledge Systems

The arrival of Muslims in India brought new medical systems, most notably Unani Tibb. This system not only flourished but also actively integrated knowledge from Arabic, Persian, and existing Ayurvedic traditions. This demonstrates a significant blending and cross-pollination of diverse medical knowledge systems, highlighting an open intellectual environment. This intellectual syncretism was not merely about the passive import of new knowledge; it signified an active and pragmatic process of blending and adapting new systems with existing indigenous ones. This suggests a highly utilitarian and open intellectual environment where the effectiveness and practical utility of knowledge superseded rigid adherence to a single, exclusive tradition. This period was marked by the coexistence and active interaction of various religious traditions and knowledge systems within the broader societal structure. Historical accounts, such as that of the Chinese pilgrim Hiuen Tsang in the 7th century AD, further underscore the prevailing tolerance among rulers towards different religions.

Motivations Behind Scientific Pursuits

Islamic scholars in India, particularly during the Delhi Sultanate and Mughal Empire, significantly enriched Indian scientific knowledge through extensive translations of texts and innovations in fields such as astronomy, optics, and medicine. Indian numerals were transmitted to the Islamic scholarship and from there diffused to worldwide transmission and the further development of mathematics, science and technology. As an example, Brahmagupta’s mathematical treatise, specifically his work "Brahma-siddhanta" was translated by Al-Khwarizmi's as "Kitab al-Jabr wa-l-Muqabala" (The Compendium on Calculation by Completion and Reduction), which is considered the foundation of algebra, through the Latin translation of it as Al Jebar which paved the way for the introduction of Indian mathematics to Europe and thus, the universalization of knowledge and development of mathematics.

These scientific pursuits were often motivated by underlying religious and philosophical considerations. A notable example is the Mughal emperor Akbar's profound interest in astronomy, which directly led to the establishment of observatories and the vigorous promotion of scientific inquiry. The Jantar Mantar in Jaipur and New Delhi are a collection of 19 astronomical instruments built by the Rajput king Sawai Jai Singh, an accomplice of the Mughal Empire. It features the world's largest stone sundial and these instruments allow the observation of astronomical positions based on the Aristotelian Ptolemaic positional astronomy operated on the three main classical coordinate systems, namely the horizon-zenith local system, the equatorial system, and the ecliptic system which was shared by many other civilizations. This patronage was often framed within a philosophical appreciation for divine harmony in the cosmos, indicating that religious and spiritual motivations continued to provide a rationale for scientific exploration. This highlights a continuity of the "science as pathway to understanding" theme from the ancient period, but with a significantly broadened by the integration of the many cultural and religious ethos towards a holistic account.

IV. Colonial India: Imposition, Tension, and Adaptation

The Colonial period through the British Raj, the conquest of India by the East India Company and which was kept under the British crown since the 1857 First Indian Revolution. This colonial period saw the introduction of Western Education, profoundly impacted the relationship between science, technology, religion, and spirituality in India. Western science and technology were introduced not primarily as tools for understanding the cosmos, but as instruments of imperial control, leading to significant tensions with indigenous traditions and unique adaptations by Indian society.

Western Science and Technology as Tools of Imperialism

The introduction and cultivation of Western science and technology in India were inextricably linked to the agenda of imperialism. The colonial state's primary motivations for promoting science and technology were overtly administrative and economic. These efforts were specifically aimed at gaining a better understanding of the country for more effective governance and, crucially, to facilitate the exploitation and systematic drainage of its vast resources. The "scientific method" itself was actively utilized as a tool of colonization, often buttressed by notions of racial superiority, and was explicitly employed to justify the extraction of resources and the subjugation of the populace. This period marks a profound and disruptive departure from previous eras. Science and technology were no longer primarily perceived as "pathways to understanding the universe" or motivated by a search for "divine harmony." Instead, they were explicitly re-purposed and became tools for governance and exploitation. This instrumentalization fundamentally altered the nature of the science-religion relationship, introducing a direct conflict not just between Western and Indian knowledge systems, but crucially, between the purpose and ethics of scientific pursuit. While Western science was introduced and new scientific institutions were established, this process was largely a unilateral projection and dissemination of Western ideas. This often occurred in a distinctly Eurocentric manner that systematically overlooked, undervalued, or dismissed India's own rich and long-standing scientific traditions. This imposition of a foreign scientific paradigm, often presented as superior, further exacerbated the tensions which enabled some intellectuals to establish organizations like Rastriya Swayam Sevak Sangh which became the impetus for the political party Bharatiya Janata Party to bring in an ideological Hindutva process. Gradually, this process now controls and govern the Indian scenario even reinterpreting the scientific, technological, the religious and democratic foundations.

Tension for Indian Scientists and Adaptation of Western Technology for Cultural Preservation

As a direct consequence of this imposition, Indian scientists during this era experienced significant tension. They were caught between the demands of Western scientific rationality and their own culturally embedded, institution-oriented Indian religious and spiritual values. They actively sought ways to resolve this inherent conflict. This shift in purpose, driven by colonial objectives, led directly to tension and conflict in the application and integration of science within Indian society.

Despite the overarching colonial agenda, technology, such as print technology imported from the West, was ingeniously adapted and utilized by Indians. This adaptation was not solely for adopting British ways; in later stages, it became a powerful tool for preserving native cultural identity and religious beliefs against mounting colonial and missionary pressures. This demonstrates significant agency and resilience on the part of the colonized. While the technology was initially intended to disseminate British ideas and values, Indians strategically used it to preserve native cultural identity and religious beliefs against colonial and missionary pressures. This highlights a dynamic interplay where technology is not a neutral force; its impact is profoundly mediated by the intentions and contexts of its users. It illustrates how technology can be a double-edged sword, capable of both facilitating assimilation into dominant paradigms and simultaneously empowering resistance and the preservation of indigenous religious and spiritual traditions in the face of external pressure. This adaptive use also foreshadows the nationalist narrative, championed by figures like Mahatma Gandhi, who explicitly emphasized the importance of spiritual values in the context of scientific and technological development, advocating for a balanced approach that respected India's cultural roots while judiciously embracing modern science.

V. Contemporary India: Incongruence, Coexistence, and Contested Boundaries

In Contemporary India, the relationship between science, technology, religion, and spirituality is characterized by complex and nuanced dynamics, often marked by a unique interpretation of secularism, a pervasive overlap in scientific spaces, and ongoing debates. A notable "incongruence between the articulated ideal and the lived reality" is observed in scientific workplaces across contemporary India. While a significant portion of Indian scientists surveyed report viewing the relationship as one of "independence" or "non-overlapping magisteria" (NOMA), a perspective often found in Western contexts, qualitative interviews reveal that religion consistently emerges and overlaps considerably with scientific work and spaces. This stands in sharp contrast to Western contexts where scientists typically maintain a strict separation between faith and the workplace.

Unique Interpretation of Secularism and its Manifestations

This pervasive overlap in India is deeply rooted in the distinct Indian understanding of "secularism," which fundamentally differs from the Western notion of strict separation of church and state. Indian secularism often translates to "equal respect for all religions" (Sarva Dharma Sambhava) and, consequently, allows for religion to be integrated into public life through the meritorious constitution of India promulgated in 1956 by the Constituent Assembly. As a result, a strict separation between religion and science is not always expected or enforced in Indian scientific workplaces. This core difference in the understanding and application of secularism is a critical causal factor for the observed "incongruence" between ideal and reality. Western secularism, generally advocating for strict separation of church and state (leading to a NOMA ideal in science), contrasts sharply with Indian secularism's principle of "equal respect for all religions." This distinct philosophical foundation directly causes and permits the institutional authorization, accommodation, and selective integration of religious practices within scientific spaces. The proposed term "commensality" or "coexistence" is a direct consequence and accurate descriptor of this unique secular framework, explaining why the lived reality in Indian scientific workplaces diverges so significantly from a Western-centric ideal of strict independence. This highlights how a nation's foundational political philosophy can deeply shape the practical interaction between science and religion.

The emergence of religion in these scientific spaces manifests in several forms:

Institutional Authorization: Religious symbols and practices are sometimes formally accepted and supported at an institutional level. This includes invocations of deities at major scientific conferences or during opening ceremonies of scientific institutes. Religious festivals are also widely celebrated on scientific campuses, often perceived by participants as cultural or social events linked to ethnicity rather than strictly religious ones.

Accommodation: There is a remarkably high degree of respect for and accommodation of religious beliefs and practices among scientists, even when these might present minor inconveniences for scientific work schedules or routines. Examples include adjusting schedules based on auspicious dates derived from religious calendars or participating in religious practices to demonstrate respect for colleagues.

Selective Integration: Individual scientists actively integrate religion into their day-to-day work lives in various personal ways. This includes having religious symbols (like idols) in offices and laboratories and performing religious practices, such as praying for the success of scientific experiments. While some nonreligious scientists may view such practices with scepticism or attribute them to a "placebo effect," they are generally observed and accepted, often with a high degree of tolerance. Discussions about religion may be avoided among diverse colleagues but are common among those who share a similar religious background.

Contested Boundaries and Unique Aspects Compared to Western Contexts

Despite the widespread prevalence of integration and accommodation, the boundaries between religion and science are not entirely static and are, at times, contested. Authority figures may occasionally limit overt institutional religious expressions. Individual scientists may also critically assess and sometimes criticize religion, viewing it as potentially detrimental to scientific pursuits. They might argue that religious passive acceptance discourages critical inquiry and conflicts with the fundamental principles of the scientific method.

The sources explicitly emphasize that the degree of religious accommodation and integration observed in Indian scientific workplaces is exceptionally rare in Western science. This complex interaction does not fit neatly into conventional categories like conflict, independence, or collaboration, leading researchers to propose new descriptive categories such as "commensality" or "coexistence," where science and religion exist in the same space without necessarily complementing or conflicting with each other.

A notable difference from some Western contexts is the relative absence of key polarizing issues like Darwinian evolution posing a significant public threat to religion in India. Debates do exist, however, concerning issues like evolution versus creationism, astrology's role in society, and the integration of traditional medicine with modern healthcare. The explicit mention of the absence of Darwinian evolution as a major public threat to religion in India is a significant comparative observation. In many Western contexts, this conflict epitomizes the perceived irreconcilability of science and religion, often becoming a focal point of public debate. Its relative absence in India suggests that the underlying epistemological assumptions about knowledge and truth, and the cultural modes of interpreting religious texts, are fundamentally different. If, as in ancient India, science and religion were both conceived as "pathways to understanding”, and if religious texts were interpreted more metaphorically, allegorically, or as containing insights rather than literal scientific claims, then a direct, public, and polarizing conflict over scientific theories like evolution is less likely to arise. This implies a greater cultural flexibility in interpreting religious texts or a different cultural emphasis on the domains of religious authority versus scientific inquiry, leading to a more accommodating stance towards scientific theories.

Influence of Socio-Cultural Factors

Beyond direct interactions, broader socio-cultural factors significantly influence the science-religion dynamic in contemporary India. There are instances where science is strategically used to lend legitimacy to religious claims or is leveraged within the broader context of Hindu nationalism. Caste remains a hidden but pervasive influence in scientific institutions, subtly affecting opportunities and perceptions of suitability for scientific careers. The deep social embedding of scientists within familial and cultural contexts, where religion plays a prominent and often central role, also significantly influences its presence and manifestation in the workplace. The inclusion of caste and Hindu nationalism as influences points to deeper, often hidden, societal forces shaping the dynamic. Caste, as a "hidden influence" affecting "opportunities and perceptions of suitability for science," implies that pre-existing social hierarchies and identities can subtly mediate access to, and participation in, scientific fields, potentially intersecting with religious identity and privilege. Similarly, the use of science to "legitimize religion" or leverage Hindu nationalism indicates a significant political and ideological dimension where science is not merely a neutral pursuit of knowledge but can be co-opted for broader socio-political agendas. These factors demonstrate that the science-religion relationship is not purely an intellectual or philosophical one but is deeply embedded in and influenced by the socio-political fabric of the nation, adding complex layers of power, identity, and ideology to the interaction.

VI. Science and Religion in India: A Unique Philosophical and Cultural Synthesis of Science, technology, religion and spirituality

In summary, science and religion in India have historically coexisted and profoundly influenced each other, culminating in a unique philosophical and cultural synthesis. Throughout much of India's history, religious beliefs frequently served as a motivation for scientific exploration, while scientific insights, in turn, enriched spiritual understanding. This often-harmonious relationship reflects India’s broader philosophical worldview, which consistently emphasizes unity, diversity, and the pursuit of holistic knowledge in terms of its ideology of unity in diversity or a vibrant mosaic of religions, cultures, languages, traditions and ethos. The trajectory has been traced from the inherent integration of the ancient period, through the syncretic blending and administrative shifts of the medieval era, the imposition and resulting tensions of the colonial period, to the unique form of "commensality" and contested coexistence observed in contemporary India, shaped by its distinct interpretation of secularism.

India's historical trajectory fundamentally challenges simplistic Western dichotomies of conflict or strict separation, offering a compelling model of "commensality" or "coexistence" where these domains frequently share the same space and influence each other. The recurring theme identified throughout the historical periods, from the ancient concept of science and religion as "pathways to understanding" to the contemporary phenomenon of "commensality" , is the overarching pursuit of "holistic knowledge". This is not merely a concluding summary point but represents a fundamental, distinguishing characteristic of India's approach to knowledge. It implies that the ultimate goal of inquiry transcends rigid disciplinary boundaries, viewing different forms of knowledge (scientific, spiritual, technological) as interconnected facets of a single, larger truth or reality. This enduring perspective offers a valuable and compelling alternative to the often-dominant Western models of conflict or strict separation, suggesting that integration and coexistence can be a viable, productive, and culturally resonant mode of interaction. This paradigm is a key takeaway that positions India as a significant contributor to the global discourse on science and religion.

Despite this unique synthesis, contemporary India continues to navigate ongoing debates, particularly concerning issues like evolution versus creationism, the societal role of astrology, and the integration of traditional medicine with modern healthcare. These discussions underscore the persistent tension between purely secular-rational approaches and those that view spirituality and religion as integral to understanding the world. While "integration" is a hallmark of the ancient period, the comprehensive historical overview demonstrates that this integration is not a static or unchanging state. Instead, it transforms and adapts significantly across different epochs: from an inherent philosophical unity (ancient) to a syncretic blending and administrative compartmentalization (medieval), to a forced tension and adaptive resistance (colonial), and finally to a unique form of "commensality" in contemporary workplaces. This highlights that the relationship between science, technology, religion, and spirituality in India is a continuously negotiated and re-defined dynamic, profoundly shaped by changing historical, political, social, and cultural contexts. The "unique cultural synthesis" is therefore best understood as an ongoing, adaptive process though there were paradigm shifts, yet didn’t evolve with a fixed outcome, requiring continuous negotiation and re-evaluation of boundaries and interactions. The ideological interventions in the political processes indeed influence the scientific and religious perspectives of the present context of India. This dynamic perspective underscores the complexity and resilience of India's approach. The Indian context, with its rich tapestry of historical, philosophical, and socio-cultural factors, provides a unique and valuable case study for understanding the diverse and dynamic modes of existence and interaction between science, technology, religion, and spirituality on a global scale.

Mathew Chandrankunnel

Published July 2025

Further reading

Ian Barbour, www.religion-online.org/book/religion-in-an-age-of-science.

New and Emerging Perspectives on SCIENCE, RELIGION AND SOCIETY A Festschrift in Honour of DR. SULAIMAN AKOREDE POPOOLA (DL), Edited by prof. R. I. Adebayo and others, Department of Religions &Peace Studies, Lagos State University, Lagos, Nigeria, 2020.

Nikhil Gulati, The People of the Indus: A Graphic Narrative on the Rise and Fall of the Harappan Civilization, Penguin, New Delhi, 2022.

Hans Henrich Hock, Vedic Studies: Language, Texts, Culture and Philosophy, D.K Print World, New Delhi, 2014.

William Dalrymple, The Golden Road: How Ancient India Transformed the World, Bloomsbury, 2024.

Suresh Chandra Ghosh, History of Education in Modern India, Orient Blackswan, New Delhi, 2013.

The Cambridge History of India: Ancient India, Turks and Afghans, The Mughul Period, British India 1497-1858, H. H Dowel, Edited by E.J. Rapson and others, 2024.

David Arnold, Science, Technology and Medicine in Colonial India, Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Shridhar Damle Walter Anderson, The RSS: A View to the Inside, Penguin, 2018.

Rekha Koul, et al. Science Education in India: Philosophical, Historical, and Contemporary Conversations, Springer, 2020.

Abhay Prasad Singh & Krishna Murari, Political Process in Contemporary India, Pearson Education, 2019.

Multidisciplinary Contributions to the Science and Creative Thinking, (Creativity in the Twenty First Century) edited by Giovanni Emanuele Corazza and Sergio Agnoli, Springer, 2015.

Mathew Chandrankunnel, Ascent to Truth: The Physics, Philosophy and religion of Galileo Galilei, in 2011.

------ Cosmosophy: The Physics and Philosophy of the Cosmos, Bangalore: Dharmaram Publications, 2014.

------ Philosophy of Quantum Mechanics, Quantum Holism to Cosmic Holism, The Physics and Metaphysics of David Bohm, Global vision Publications, June 2008.

Picture Credits

map by Anna Polishchuk (c) Adobe Stocks #3155264

Panorama of Indus valley in Himalayas. Ladakh, India by Dmitry Rukhlenko (c) Adobe Stocks #73945285

Indian zodiac by Juulijs (c) Adobe Stocks #54970123

Church of St. Cajetan; Goa, India by lenkusa (c) Adobe Stocks #62133404

Sculpture of Maitreya buddha at Thiksey Monastery by zephyr_p (c) Adobe Stocks #84595164

Tempel in Indien by Karsten Thiele (c) Adobe Stocks #10241961