Who Are We, and Where Are We Going?

Ronald Cole-Turner

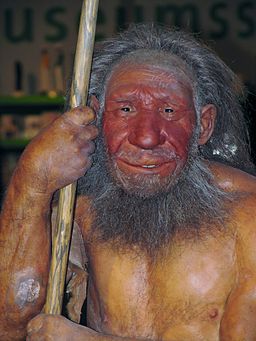

The question of human evolution is really many questions at once. It is, first of all, a scientific question about our past. When did anatomically modern humans first appear? What were the pathways of human migration? Did modern humans interbreed with other closely-related forms of human life, such as Neandertals or the recently-discovered Denisovans?

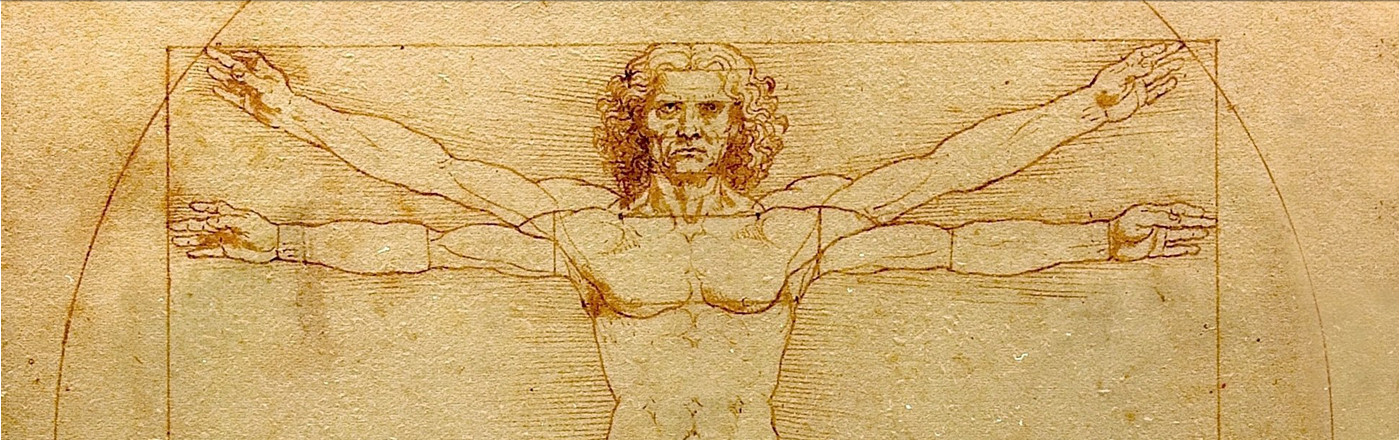

Such scientific research involves experts in many disciplines, from archeology to genetics. In the past few years, this research has advanced rapidly and has taken many unexpected turns. With each scientific advance comes new philosophical and religious questions. What distinguishes us from other forms of life? Are we biologically "unique"? Does evolution account for everything about our human nature, or does the human "mind" or "soul" require some explanation beyond biological science?

The Rise of Art and Culture

One way to approach these questions is to study the rise of art and culture. It seems that modern human first emerged as a distinct species some 200,000 years ago. Like the other forms of humanity from which we emerged, we were using simple tools. Slowly over time, the technology of these early modern humans advanced. One critical period seems to be about 100,000 years ago, about the time that modern humans migrated out of Africa. We know that at about the same time, humans were mixing paint pigments and creating beads from shells.

Another period of fairly intense technological and cultural development seems to have occurred between 40,000 and 30,000 years ago. During this period, modern humans displaced Neandertals in Europe and western Asia. Cave art begins to appear. The oldest art known today consists of simple circles in a cave in northern Spain, dating back just beyond 40,000 years. Then handprints appear, and then the magnificent paintings of the Chauvet Cave in southern France, recently shown in the documentary by Werner Herzog ("The Cave of Forgotten Dreams").

Simple bone flutes also date back about 40,000 years. This seems to have been the beginning of a time of great change for modern humans, not just because of cultural and technological advance but also because of the disappearance of the Neandertals.

Recent Advances in Genetics

Thanks in part to recent advances in genetics, it is now possible for scientists to reconstruct an extremely high-quality genome for Neandertals and other forms of archaic humans, such as the recently-discovered Denisovans. Their DNA can be compared with modern human DNA. The result, accepted by most researchers in the field, is that modern humans interbred with Neandertals and Denisovans. Many human beings alive today carry DNA that entered the human gene pool from these other forms of humanity.

These discoveries are occurring rapidly, sometime so rapidly that it is hard to incorporate them into our collective understanding of who we are as a species. Never before has our knowledge of our past come so quickly. How do we see ourselves in light of these discoveries? Given these findings, what does it mean to be human? Do we include Neandertals and Denisovans in our definition of humanity? Were the Neandertals capable of sophisticated culture, language, or self-awareness? Such questions drive new research that asks about Neandertal art and technology.

The Question of Human Evolution

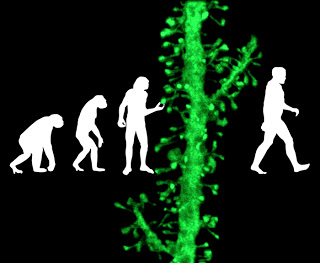

But of course, the question of human evolution is not just a question of the past or even just a question of the present. It is also a question of the future. We look back to ask: Where have we come from? We look at ourselves today to ask: Who are we? How do we understand our diversity? But we also look forward to ask: Where are we going?

Looking back, we see the slow but extraordinary rise of human culture. We see how technology has transformed us. Not very long ago, we lived in simple groups as ape-like creatures. Now we are urban, our minds merged with machines and our lives saturated with technology.

Some have suggested that human biological evolution has stopped but that human technological evolution has only just begun. In the 1950s, for example, Teilhard de Chardin and Julian Huxley both suggested that technology will take human evolution to a whole new level, transforming us into a new species. Today, their ideas are advocated by "transhumanists," who advocate free development and unrestricted access to these technologies. They see technology as a way to get around the limits of our biology. Can we make the brain smarter, the body stronger, or our lives longer? If so, why would anyone object? No one, they say, should be opposed to the idea that human beings could become better than we are, that we could enhance ourselves even to the point of become more than merely human.

But many people do object to what they see as attempts to go beyond evolution. They fear what might go wrong. Some argue that real enhancement is not possible. It always comes with too many negative consequences or side effects. Others fear that enhancement may actually be possible. We may figure out how to become not just stronger but truly healthier, for example. Their concern is not that we will fail at enhancement but that we succeed in becoming stronger or smarter or living much longer. What then?

Where are we going?

These are questions first of all for science and technology. Is any of this really possible? But they are also questions for philosophy, ethics, and theology. Is any of this right or good? Is it "playing God," an act of ultimate defiance? Or is it the way God creates, and continues to create even now, through human knowledge and technology? Should humans create the technologies that make enhancement possible?

Today we find ourselves swept along all too quickly by new technologies, some of them clearly pointing in the direction of human enhancement. Almost daily we learn of advances in cell biology, nanotechnology, synthetic biology, and information technology. As these develop and converge, they become increasingly powerful tools for remaking nature, including human nature.

Two things are happening at once. First, we are learning about our past more quickly than ever. Second, we are inventing tools for human transformation more rapidly than ever. It is as if we are re-discovering and re-inventing ourselves all at once and at a speed too high to comprehend.

At the very least, our challenge is to become more clearly conscious of our moment in history. It is as if we are living in that intense period between 40,000 and 30,000 years ago, but with the pace of change accelerated perhaps a million-fold, probably much faster. In the entire 200,000 year history of our humanity, our moment is the most transformative and the most perilous. Who are we, and where are we going?

Ron Cole-Turner

Published January 2013

We also provide a German translation of this article.

The Rev. Dr. Ronald Cole-Turner is the H. Parker Sharp Professor of Theology and Ethics, a position relating theology and ethics to developments in science and technology. He is an ordained minister of the United Church of Christ, a founding member of the International Society for Science and Religion (currently serving as vice president), and has served on the advisory board of the John Templeton Foundation and the Metanexus Institute. Cole-Turner is the author of Transhumanism and Transcendence: Christian Hope in an Age of Technological Advancement,The New Genesis: Theology and the Genetic Revolution, the co-author (with Brent Waters) of Pastoral Genetics: Theology and Care at the Beginning of Life, the editor of Human Cloning: Religious Responses and of Beyond Cloning: Religion and the Remaking of Humanity, the co-editor of God and the Embryo: Religious Voices on Stem Cells and Cloning, editor of Design and Destiny: Jewish and Christian Perspectives on Human Germline Modification, and editor of Technology and Transcendence (in press).

Picture Credits

Hands touching #22626567 © Andrea Danti - fotolia.com

Reconstruction of Neandertaler at Neanderthal Museum @ Wikimedia Commons

The Panel of Hands, El Castillo Cave, Spain. Image courtesy of Pedro Saura.

Photo courtesy of The Scripps Research Institute

#42638169 © Sergey Nivens - fotolia.com